PADRE PIO

Childhood and adolescence

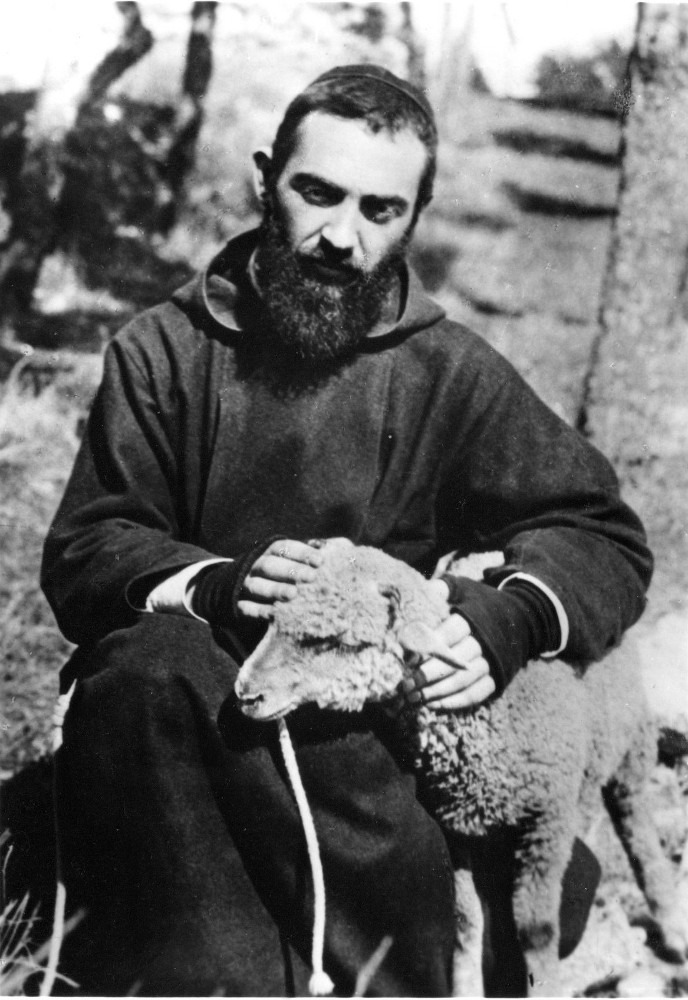

Padre Pio, known as Francesco Forgione before he became a friar, the son of Grazio Maria and Maria Giuseppa Di Nunzio, was born on 25 May 1887 in Pietrelcina (in the province of Benevento, Italy) and the following day was baptized in the Parish Church of Our Lady of the Angels. His childhood, spent quietly in a modest Christian family environment, was not marked by any noteworthy events. However, some precursory signs are not lacking which were to make known throughout the entire world that remote little town in the province of Benevento.

Francesco was barely five years old when he began to cherish the idea of consecrating himself to God for ever, with an impulse of fervour rarely found at that age, and probably without a full awareness of what was involved in such a binding and transcendental act. At this same age the first charismatic gifts and the devil’s first violent attacks occurred: “Ecstasies and apparitions”, one of his spiritual directors testifies, “began in his fifth year, when he had the idea and desire of consecrating himself for ever to the Lord, and these things were continual. When questioned as to why he had hidden them for so long (until 1915) he frankly replied that he had not made them known because he thought such things happened to everyone[ … ]. When he was five years old, the diabolical apparitions also began”.

It was perhaps at the age of eleven that he approached the Eucharistic table for the first time, according to the custom in those days, and on 27 September 1899, with ineffable spiritual joy, he was confirmed (cf. Letter 189).

After the third grade at primary school, his studies suffered an interruption, but were resumed later at a private grammar school as far as third grade. Towards the companions of his own age Francesco was reserved without being peevish. He preferred to withdraw from their company. In the village he was known to all for his exemplary conduct and his attendance, morning and evening at the parish church.

(All from: Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, Letters I, Biography)

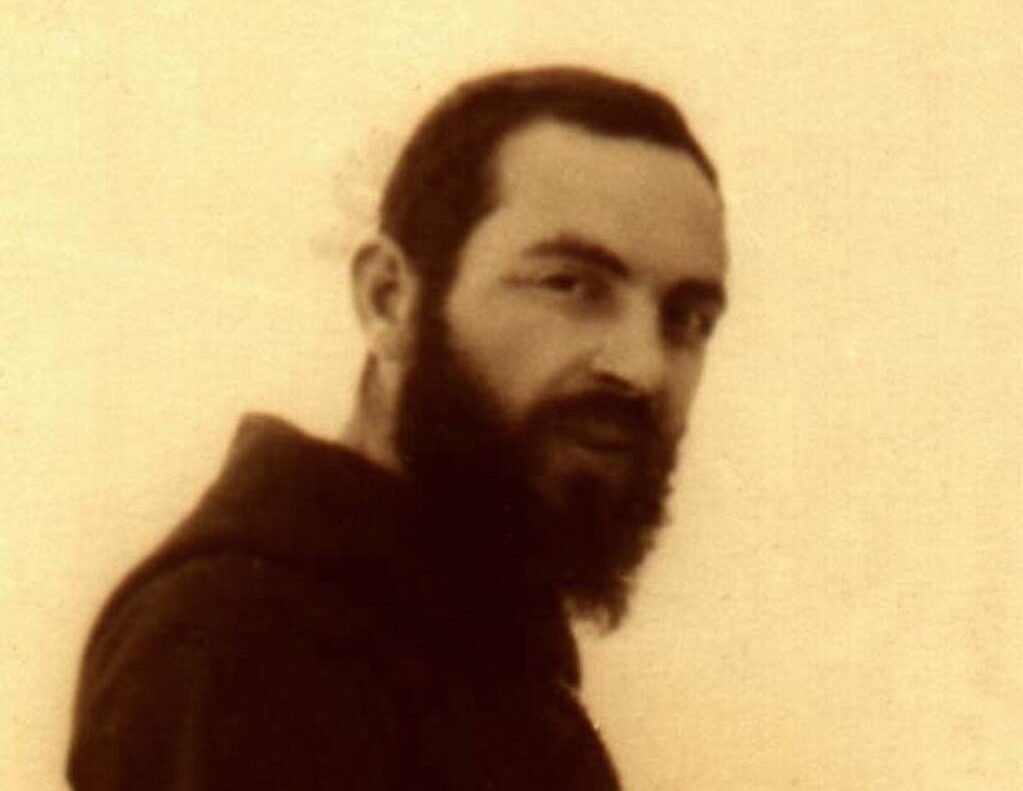

Religious vocation

Ecclesiastical studies

Immediately after his profession of simple vows Fra Pio took up the studies necessary for the priestly state: rhetoric at Sant’Elia in Pianisi, philosophy at San Marco la Catala and Sant’Elia in Pianisi theology at Serracapriola, taught by Padre Agostino of San Marco in Lamis, and later at Montefusco and Gesualdo. Nothing new was noted in his interior life at that time but as he himself says later, divine charisms were not lacking. On 10 October 1915 he wrote to his director:

“Your first question is that you want to know when Jesus began to favour his poor creature with heavenly visions. If I am not mistaken, these must have begun not long after the novitiate.”

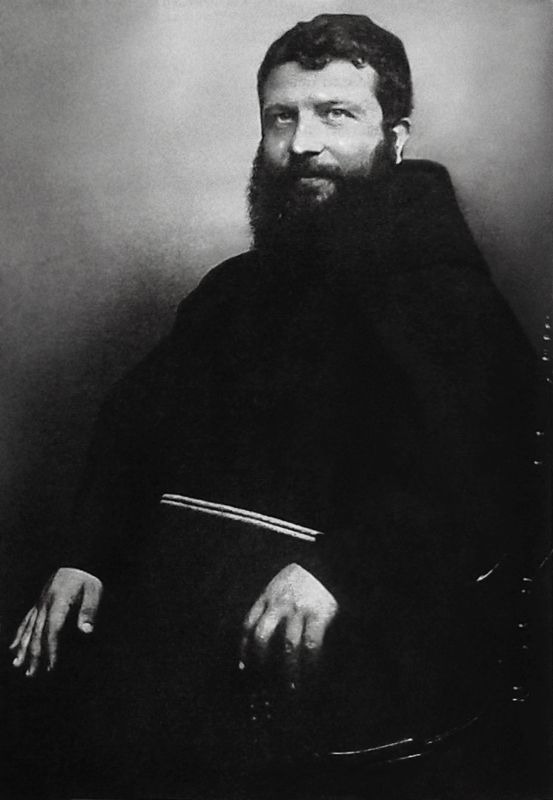

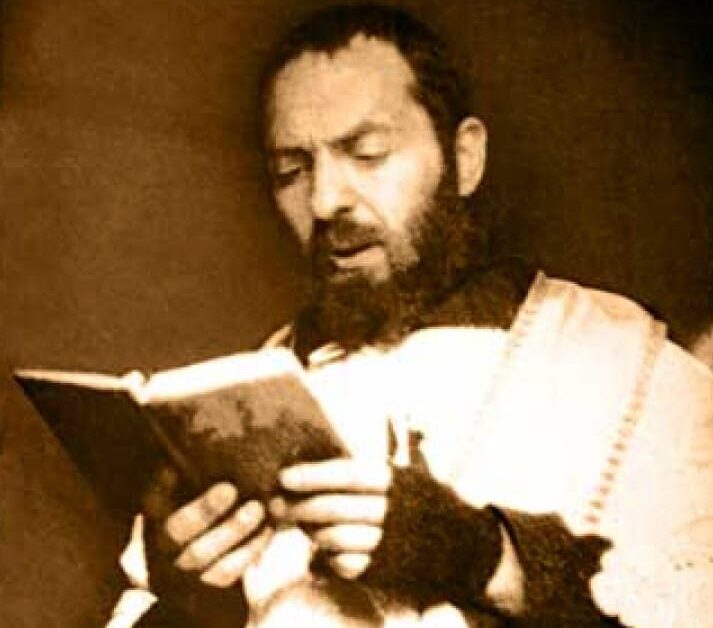

Holy Orders

In his second year of theology, Fra Pio received minor orders (19 December 1908) and the sub-diaconate (21 December 1908) in Benevento. He was ordained deacon in the friary church of Marcone on 18 July 1909 and received priestly ordination in the canons’ chapel in Benevento cathedral on 10 August 1910. He celebrated his first high Mass in Pietrelcina on the 14th of the same month.

Residence in Pietrelcina

Ill-health obliged Fra Pio to interrupt the regular course of his studies. In the hope that the change of air would help to restore his health, the doctors and his superiors sent him to his native village about the middle of May 1909. Here, with the exception of a few brief intervals, he remained until 17 February 1916, struggling continually and vainly against the mysterious illness which racked his frail body. This was a time of intense interior life and of persevering ascent by the arduous paths of the spiritual journey as is abundantly illustrated in the first part of the letters.

Towards the middle of October 1911, after an examination by the well-known doctor, Antonio Cardarelli, Padre Pio was accompanied by the Provincial, Padre Benedetto of San Marco in Lamis, to the friary of Venafro (province of Campobasso), in which community he was to remain. But his illness took an alarming turn for the worse and, in order to avert imminent disaster, he was brought back to Pietrelcina on 7 December. Next day, to everyone’s astonishment, he said Mass in the parish church “as if he had not been ill at all.”

The words in inverted commas were pronounced by Padre Agostino, who has left us the following notes on Padre Pio’s brief stay at Venafro:

” The Father Guardian at that time, Padre Evangelista of San Marco in Lamis, accompanied him to Naples for a medical examination. The doctors understood very little. At Venafro in November 1911 Padre Evangelista and myself became aware of the first supernatural phenomena. I assisted at several ecstasies and many diabolical molestations. I wrote down at the time all that I heard him say during the ecstasies and the manner in which the devil molested him[ … ]. While he remained at Venafro he lived on the Eucharist alone, both when he celebrated Mass himself and when he received Holy Communion but was unable to say Mass”.

Padre Benedetto, his Provincial, viewed with disfavour Padre Pio’s prolonged stay in his own home and for Padre Pio this gave rise to unpleasantness and severe suffering. But since his return to community life was not possible, the Provincial obtained for him on 5 March 1915 a rescript from the Holy See which authorized him to remain “outside the friary in order to take care of his health, as this was the only means which afforded hope for his recovery”. He was to continue to wear the Capuchin habit and remain under obedience to the Provincial Superior. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 threw the Capuchin province of Foggia, like all other Italian provinces of the Order, into great confusion, as many of the friars were called up for military service. Padre Pio also reported to the recruiting office in Benevento on 6 November 1915 to fulfil his duty as a citizen and, on 6 December, was assigned to the 10th Medical Corps in Naples. But by the 18th of that month he was already at home on convalescent leave for a year. Meanwhile his superiors were bringing increasing pressure to bear on him to make him return to community life. A devout lady in Foggia, Raffaelina Cerase, asked for him to come to that city to assist her in a serious and alarming illness. This request afforded the Provincial Superior the chance to send Padre Pio a letter of obedience, but without revealing all the circumstances.

From Foggia to San Giovanni Rotondo

The pious desire of this lady, Raffaelina Cerase, was the lawful pretext for his superiors to recall Padre Pio and keep him in community life for good. Thus, on the afternoon of 17 February 1916, having left Pietrelcina that morning, he arrived at the Friary of Sant’Anna in Foggia and became a regular member of this community.

Next day he visited the sick lady for the first time (she died on 25 March) and from that moment a new and fruitful stage of his ministry began.

The city air, however, was obviously unsuited to his poor health.

On 28 July he went up to stay for a few days at the nearby friary in San Giovanni Rotondo where the climate proved more suitable. Early in September, therefore, Padre Benedetto, the Provincial, allowed him to transfer temporarily to that friary and the “temporary” transfer became permanent. Here Padre Pio was to remain until his death, a period of fifty-two years.

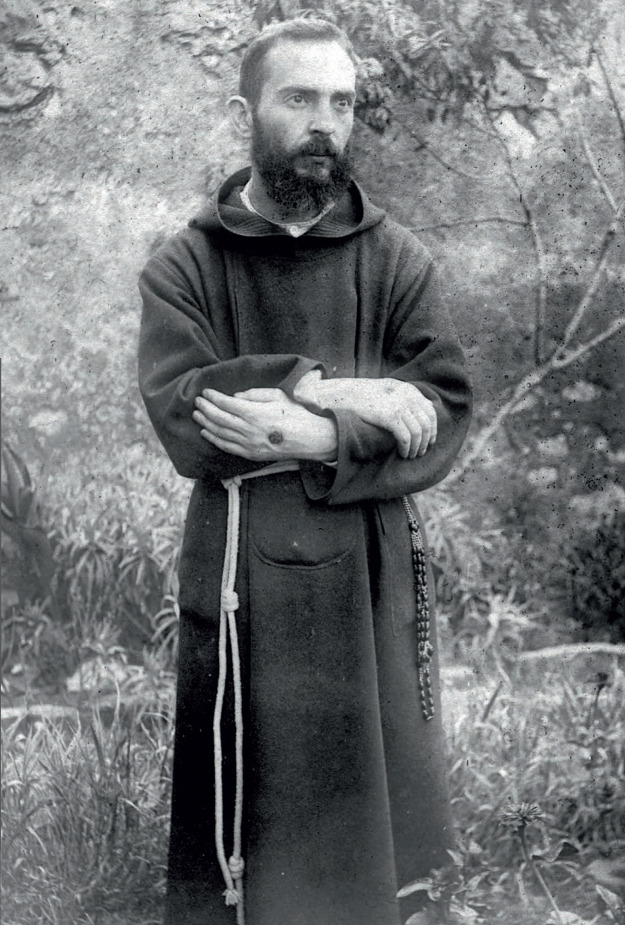

The stigmatization.

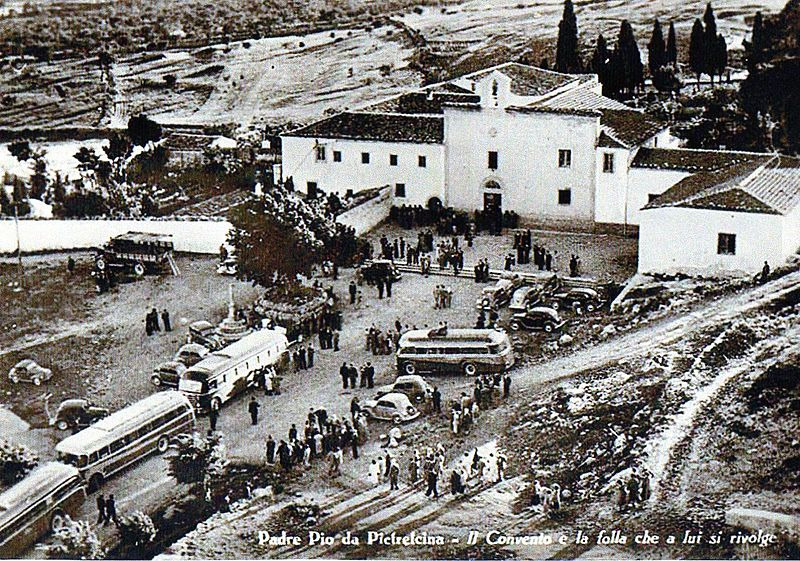

Crowds flock, to the spot.

Padre Pio’s life during this long period of six years (1916-1922) was marked, not by the external facts just related but by his spiritual progress, with which we shall deal in a later chapter of this introduction. We mention here just a few mystical phenomena which serve to explain the other events.

On 30 May 1918 Padre Pio received one of the more noteworthy “substantial touches”, the “wound of love”, which produced marvellous effects. On 5-7 August of the same year the mystical phenomenon known as transfixion or transverberation of the heart took place, a prelude, we may say, to the prodigy of the stigmata which occurred a little over a month later (20 September) and which marked a decisive turn in his life.

Despite the prudent and strict reserve maintained by Padre Pio and his superiors, this fact could not be hidden and it gradually became public property. We know the enormous effects of prodigies of this nature on the faithful. Hence, at first almost secretly in the surrounding towns, then in places further afield and even quite far away, with a great hubbub – especially when the event reached the newspapers – countless crowds began to flock to the remote Capuchin friary. This was the beginning of a manifold and most effective priestly ministry.

The stigmatization not only stirred up devotion among the people but also aroused the curiosity of scientists. In particular, it attracted the attention and concern of the competent authorities. In the middle of May 1919 Dr. Luigi Romanelli, topranking physician of the civilian hospital in Barletta, was sent to San Giovanni Rotondo by the Provincial, Padre Benedetto, to examine the extraordinary event from a scientific point of view. Two months later, on 26 July, it was the turn of Prof. Amico Bignami, professor of pathology at Rome University who, on behalf of the Roman ecclesiastical authorities, repeated the examination for a week. In the same year 1919 a third examination was carried out by Dr. Giorgio Festa, on 9 October. This doctor had been sent expressly to San Giovanni RotondO’ by the Capuchin Superior General. On 15 July of the following year Dr. Festa repeated the examination, this time together with Dr. Luigi Romanelli.

Obviously the opinions and conclusion of the scientist and the press could not agree as to the origin and nature of the stigmata. Nevertheless, esteem and veneration for the “stigmatized friar of Mount Gargano” increased as the days passed. Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, Secretary of State to His Holiness the Pope, in a letter of 19 November 1919 recommended a number of persons to Padre Pio and was happy to learn that he would pray “for the Holy Father and for me, who have great need of these prayers” (cf. Letter 579).

On 24 March 1920 the Archbishop of Simla, Most Rev. E.E.J. Kenealy, went to San Giovanni Rotondo. His visit produced wide echoes in the English Press. On 28 May of the same year came Mgr. Bonaventura Cerretti (later a cardinal), titular Archbishop of Corinth and Secretary for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs at the Vatican.

On behalf of Pope Benedict XV, in July of that year, the Procurator General of the Passionist Fathers, Father Luigi Besi, arrived along with the well-known doctor. Professor Bastianelli. The Holy Father said at the time that Padre Pio was one of those extraordinary men whom God sends from time to time for the conversion of men. On 25 October 1921 came the visit of Cardinal Sili, Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Segnatura and Apostolic Delegate at the Shrine of Pompei. The Cardinal was accompanied by Monsignor Giuseppe De Angelis of the same apostolic delegation.

End of spiritual direction by Padre Benedetto

Meanwhile, towards the end of 1921, someone had circulated the rumour that Padre Pio was likely to be transferred and the inhabitants of San Giovanni Rotondo had risen up in threatening fashion. On the other hand, the daily newspapers, not always truthful, helped to swell the numbers who flocked to the spot in increasingly unruly throngs.

Even though the great majority of the visitors were devout, calm and animated by sincere faith, there were also acts of fanaticism and imprudent behaviour by some who were drawn there by mere curiosity. In order to prevent abuses and clarify the situation which had been created around the friary in San Giovanni Rotondo, the Holy Office intervened and communicated to the Superior General of the Order some regulations which were to be sent to the local Guardian. This document was dated 2 June 1922 and stipulated that Padre Pio was to be “kept under observation”, that “everything of a singular and sensational nature was to be prevented”, that he was not to celebrate Mass at a fixed hour, but at different hours “preferably very early in the morning and privately”, he was “not to bless the people”, “on no account was he·to show the alleged stigmata, to speak of them or allow people to kiss them”. It was also considered advisable that he should have another spiritual director in place of Padre Benedetto of San Marco in Lamis, “with whom he was to cease all communication even by letter.”

Limitation of pastoral ministry

During the ten years following on this first intervention by Rome, Padre Pio’s life was marked by a number of painful events. As might have been foreseen, the carrying out of the orders received from the superiors was not free from difficulty. Despite the goodwill and sincere desire of those who had to obey, they did not succeed in calming the people who were unwilling to be deprived of Padre Pio’s spiritual assistance and who set themselves up in determined fashion to oppose his possibile transfer elsewhere. It became necessary to yield in the face of certain external factors, although there was no question of disobeying the orders received from those in authority.

On the other hand, repeated admonitions arrived from Rome. In a decree dated 31 May 1923, the Holy Office stated that, after due investigation, “the facts attributed to Padre Pio were not found to be supernatural and the faithful were exhorted to abide by this declaration.” The same exhortation was repeated on 24 July of the following year, 1924, and on 23 April and 11 July 1926.

Padre Pio was ordered, moreover, not to celebrate Mass in public, but privately in a chapel inside the friary with nobody present from outside the community. He acted thus on 25 June 1923, but the following day his superiors had him go down once more to celebrate Mass in the public church, because of the dangerous reaction of the local people.

The situation became more complicated by reason of the external factors already mentioned and in 1927, from 26 March to 5 April, Monsignor Felice Bevilacqua of the Roman Vicariate carried out an apostolic visitation in San Giovanni Rotondo. A similar visitation was made in July of the following year, this time by Monsignor Bruno from the Congregation of the Council. Finally, on 23 May 1931, the Holy Office entrusted the Father General of the Capuchins with the task of applying the decree which had been approved on 13 May, namely, that “Padre Pio was to be deprived of all his priestly faculties with the exception of Mass, which he was allowed to celebrate only in private in the internal chapel of the friary”. From 25 May 1931 the friary of San Giovanni Rotondo passed under the direct jurisdiction of the Superior General.

During this painful period, despite the uproar which had arisen around him, Padre Pio persevered in solitude, prayer and suffering, submitting at all times with great confidence to the will of his immediate and higher superiors although this was for him a source of deep suffering.

Resumption of priestly ministry

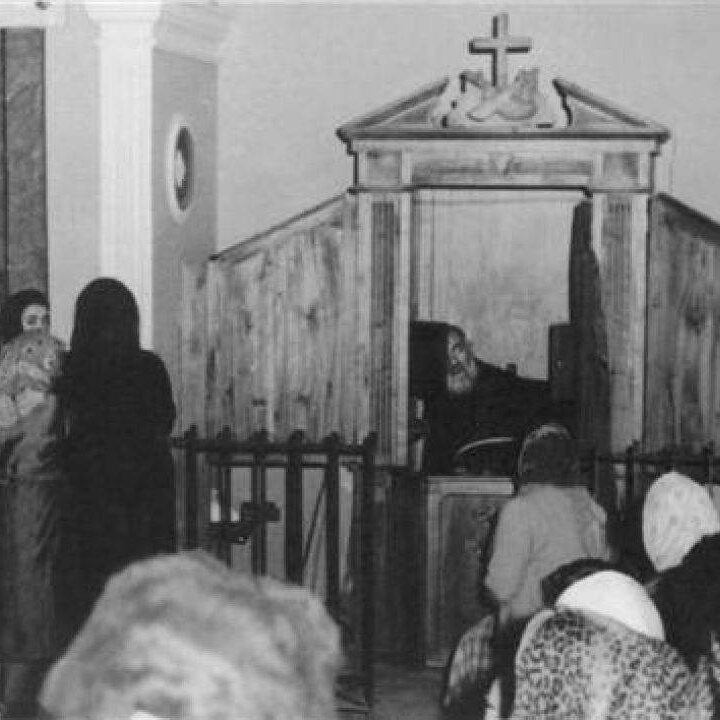

On 16 July 1933 Padre Pio again celebrated Mass in public. From 1934 he resumed the hearing of lay people’s confessions, first the men’s confessions (25 March) and then those of the women (12 May). At last, after more than ten years, his life resumed its normal course.

At the end of World War II the crowds that flocked to him grew bigger and bigger. From 7 January 1950, in order to avoid difficulties arising from the tumultuous throngs, the system of “booking” for confession to Padre Pio was introduced.

The little friary church had become unsuitable and inadequate for the needs of divine worship, due to Padre Pio’s presence and activity. Plans were made to extend it, but this idea was abandoned later in favour of a project for a large new church. The latter was solemnly consecrated by Mgr. Paolo Carta, Bishop of Foggia on 1 July 1959 and on the following day Cardinal Tedeschini crowned the image of Our Lady in the church. Padre Pio had previously said Mass many times in the open air in the square in front of the friary in order to cater to the needs of the faithful.